This post discusses host to host communication in networking. It constitutes Lesson 3 of the module How data flow through the Internet. This lesson looks at everything hosts do to send and receive data on the wire. Key concepts discussed in this post include the Address Resolution Protocol (ARP), how hosts in the same network communicate, and how hosts in different networks communicate.

- Learning objectives

- Host to host communication in networking

- Hosts connected directly to each other

- Hosts connected through a router

- Key lesson takeaways

- Key references

You may also be interested in How data flow through the Internet.

Learning objectives

- Understand how ARP resolves IP addresses to MAC addresses

- Understand how hosts in the same network send and receive data

- Understand how hosts in different networks communicate over the wire

Host to host communication in networking

A host is a computer or other device connected to a computer network and which sends or receives traffic. In typical network traffic, two hosts in communication are often called client and server. The client initiates a request and is looking to acquire some data or a service. The server is the entity receiving the request and has the data or service that the client wants.

A computer participating in networks that use the Internet Protocol suite may also be called an IP host. Specifically, computers participating in the Internet are called Internet hosts. (Host, 2022)

Hosts run software and applications for the end user to interact with, and they also at some point need to put bits on a wire. As such, it is said that Hosts operate across all seven layers of the OSI model. (Ed Harmoush, April 12, 2020)

This discussion will focus on host to host communication, explaining each step involved in the process. Two scenarios are considered:

1. Hosts connected directly to each other. Scenario 1: hosts communicating to another host in the same network. All the steps hosts take to communicate to other hosts on the same network regardless of how they are connected – whether host A is directly connected to host B or whether there is one switch or multiple switches in between.

2. Hosts connected through a router. Scenario 2: hosts communicating to another host in a foreign network. What a host does to speak to any other host on a foreign network – whether what hosts are trying to speak to is on the other side of one router or multiple routers or on opposite sides of the Internet.

Hosts connected directly to each other

Although it is rare to find situations where two hosts are connected directly to each other, understanding what happens if they were is crucial to understanding everything else that happens when multiple hosts are communicating through a switch or router. (Ed Harmoush, October 20, 2020)

This section discusses everything hosts do to communicate with other hosts in the same network regardless of how they are connected. We will examine how two directly connected hosts, A and B, communicate.

Host A has some data it wants to send to host B. Host A and host B are directly connected to each other. The two hosts do not know whether they are directly connected or whether there are hubs or switches in between. Each host has a NIC and therefore a MAC address (for convenience, only the first four digits of the MAC addresses are shown). Both hosts are configured with an IP address and a subnet mask (255.255.255.0). A subnet mask identifies the size of particular network. This is done through the process of subnetting.

Host A knows the IP address of host B – it knows it because perhaps a user jumped on the command prompt and typed ping 10.1.1.33 thus providing host A the IP address of host B or perhaps host A acquired the IP address through DNS (Domain Name System), a protocol which converts a domain name into an IP address. Further, host A knows the destination IP address 10.1.1.33 is on its own IP network. Host A will know this by looking at its own IP address and comparing to its own subnet mask to determine how many other IP addresses are on the same network (host A will know this through subnetting).

Host A can create a L3 header to attach to the data it wants to send to host B, i.e., to accomplish end to end delivery. The L3 header will include the IP address of host A (the source) and the IP address of host B (the destination).

L3 cannot interact with the wire. We need L2 for that. So host A needs to add a L2 header to this packet. But host A does not know host B’s MAC address. Host A is going to have to figure out the MAC address of host B on its own. Host A must use the ARP to resolve host B’s MAC address. ARP links a L3 address to a particular L2 address.

Host A will send out an ARP request which asks for the MAC address associated with the target IP address (10.1.1.33). Host A will include its own IP address and MAC address in the ARP request which will allow host B to directly respond to host A.

The ARP request includes a L2 header which is meant to take the ARP payload and get it delivered to host B. But that L2 header does not have a destination MAC address of host B. The ARP request is sent as a broadcast, i.e., to everyone on the network. As such, it has a destination MAC address of all f’s (ffff.ffff.ffff), which is a specially reserved MAC address for broadcasts (sending a packet to everyone on a local network).

ARP mappings are stored in an ARP cache (ARP table). Every device which has an IP address has an ARP cache. Hosts A and B both have an IP address and therefore both have an ARP cache.

Initially, host A’s ARP cache states that we’re trying to resolve the 10.1.1.33 IP address to a particular MAC address. Host B’s ARP cache is empty. When host A’s ARP request makes it across the wire to host B, host B’s ARP cache begins to populate an entry: the IP 10.1.1.22 maps to the MAC address a2a2. In the original ARP request host A provided its own MAC address.

Host B now sends back an ARP response which includes the mapping host A was trying to resolve, i.e., the MAC address b3b3 associated with the IP address 10.1.1.33 . The ARP response is sent unicast, meaning directly back to host A. Since host B knows the MAC address of host A, it can create a L2 header which will take the ARP response directly to host A.

Host A can now create the ARP mapping which was listed in the ARP response. Now host A has all the information it needs to create a L2 header for the data is was trying to send to host B. The L2 header is going to include a source MAC address and destination MAC address. The L2 header will accomplish the goal of hop to hop delivery.

Upon arriving to host B, host B will discard the L2 header as it has fulfilled its purpose of NIC to NIC delivery and is no longer needed. Likewise host B will retire the L3 header as it too has fulfilled its purpose of delivering the packet from host A to host B. Now the application on host B can process the data it has received.

Any further communication between host A and B can happen easily, as they both now have the information they need to create L2 and L3 headers.

Hosts connected through a router

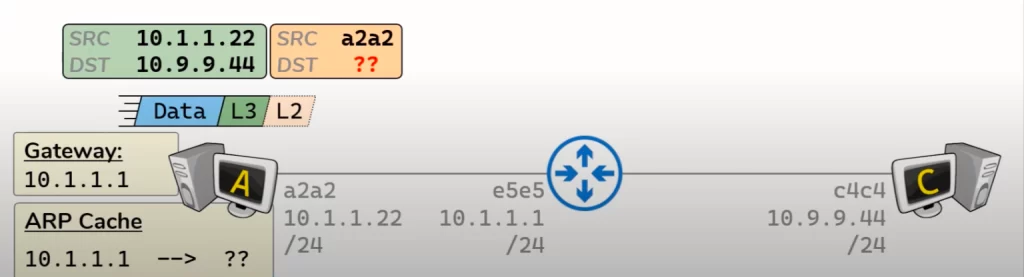

This section discusses everything hosts do to communicate with other hosts in foreign networks regardless of how they are connected. We’re going to use the following topology to understand everything host A does to send data to host C.

Both hosts A and C and the router have a MAC address and an IP address. The slash 24 (/24) is a way of representing the subnet mask 255.255.255.0. A subnet mask defines how big is a network.

Focusing on host A: it has some data to send to host C. Host A knows host C’s IP address (it was provided by the user or the application that is creating the data to be sent to host C). Host A knows the destination IP address is on a foreign network – it knows this by looking at its own IP address and subnet mask and comparing it with the target IP address.

Hence host A is able to create a L3 header identifying the two endpoints of the communication. The L3 header contains the IP address of host A and the IP address of host C. Host A needs to create a L2 header to transport the package to the next hop.

Since the communication target is on a foreign network, our next hop is the router. So the purpose of the L2 header is to transport the packet to the router. But since host A’s ARP cache is empty, it is not able to complete the L2 header.

Host A will have to use ARP to resolve the MAC address of the router.

But how does host A know the router’s IP address? The router’s IP address is already configured on host A as host A’s default gateway. When you connect a computer to the Internet, there are three things you have to configure: an IP address, a subnet mask, and a default gateway. On a Windows computer if you type C:\> ipconfig into the command prompt you will see these three things listed. (The default gateway is the IP address of our router – that’s the IP address that host A will need to resolve with ARP.)

So host A will send out an ARP request with the general message: “if anyone out there has the IP 10.1.1.1 send me your MAC. My IP / MAC is 10.1.1.22 / a2a2” – i.e., the ARP request will ask for the MAC address that correlates with the router’s IP address. When the ARP request gets to the router, the router will generate a response that includes the mapping that host A was interested in learning – “I am 10.1.1.1 my MAC is e5e5.”

When the ARP response arrives on host A, host A is able to populate its ARP cache with the mapping for its default gateway. It can use the mapping to complete a L2 header, with the router’s MAC address as the destination. Recall, it’s L2’s job to deliver data from one hop to the next. L2 uses MAC addresses for this process.

In our example, host A wants to send some data to host C, so host A creates a L3 header with its IP address as the source IP address and host C’s IP address as the destination IP address. The ARP process is necessary to create L2 headers that encapsulate the L3 packet and move it from hop to hop to its final destination.

Upon receiving the packet, the router will discard the L2 header. Now the router will add a new L2 header to deliver its payload to the next hop, whether that hop is directly to host C or is across multiple routers on the Internet.

The ARP entry that host A resolved in order to get the packet to the router can be reused to speak to any host in foreign networks. Suppose our router is connected to the Internet and a terminal on the Internet is our new destination, host D with an IP address 10.8.8.55.

In this case, host A needs to create a new L3 header with the new destination IP address of host D. But the L2 header does not need to change, as host A’s first hop is going to be to the first router. So the ARP process to resolve the router’s IP address needs to happen only once.

The first step any host takes when it’s trying to send data on a network is to determine if the target IP address is on its local or foreign network. If it’s trying to speak to a host on the same network ARP will try to resolve the target IP directly (the first scenario). If it’s on a foreign network ARP will try to resolve the gateway’s IP address (Scenario 2).

Key lesson takeaways

- The steps a host takes when speaking to another host on the same network

- steps are the same regardless if there are switches or hubs

- What hosts do to speak to hosts on a foreign network

- steps are the same whether what hosts are trying to speak to is on the other side of one router or multiple routers

- ARP’s role in this host to host communication process

- how L2 and L3 headers are populated to get the data to the other host

Key references

Ed Harmoush. (April 12, 2020). Key Players. PracNet

Ed Harmoush. (October 20, 2020). Host to Host Communication. PracNet

Related content

Compliance frameworks and industry standards

How to break into information security

IT career paths – everything you need to know

Job roles in IT and cybersecurity

Network security risk mitigation best practices

The GRC approach to managing cybersecurity

The penetration testing process

The Security Operations Center (SOC) career path

Back to DTI Courses